Twenty-five years after the adoption of United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325, a historic and transformative milestone that recognized, for the first time, that women are not just bystanders in conflict, but essential actors in building and sustaining peace. The Resolution affirmed what many had always known to be true: when women participate meaningfully in peace processes, societies are more stable, more inclusive, and more secure.

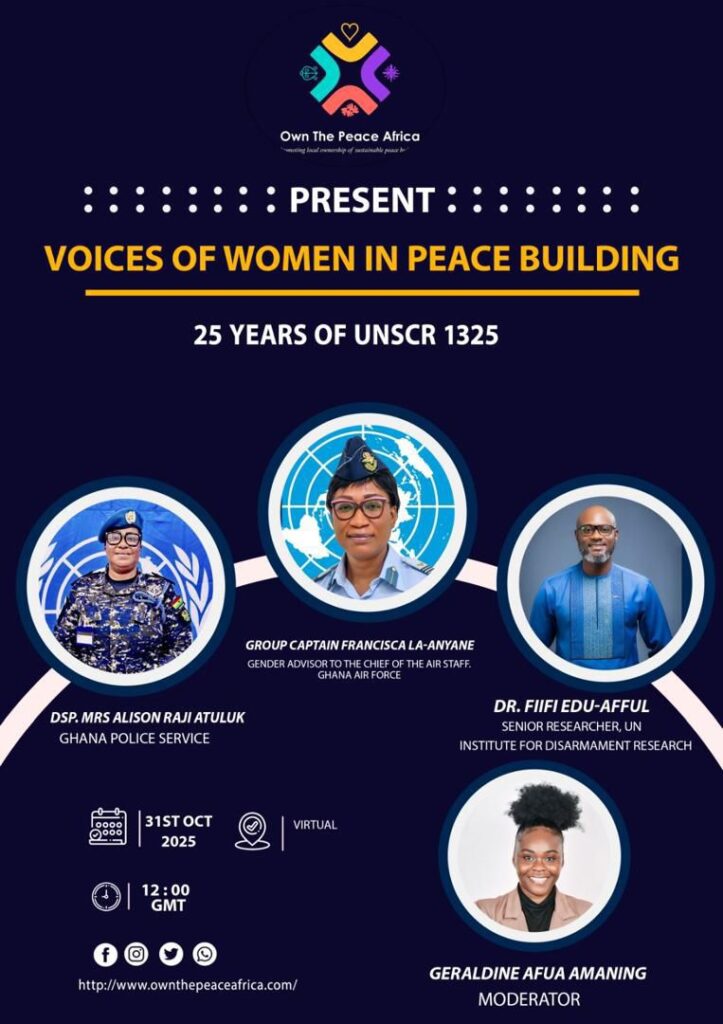

The global community continues to witness how women shape peace in ways that transform families, communities, and nations. Despite this, women’s roles in formal peace processes remain undervalued and underrepresented. To confront this ongoing gap and renew momentum behind the Women, Peace and Security agenda, Own the Peace Africa convened an online dialogue last Friday bringing together Group Captain Francisca La-Anyane of the Ghana Armed Forces, a Gender Advisor with over 22 years of service and extensive UN peace support experience; DSP Mrs. Alison Raji Atuluk of the Ghana Police Service, a distinguished peacekeeper currently serving with MINUSCA in the Central African Republic and the first woman to command the UN parade there; and Dr. Fiifi Edu-Afful, a peace and security scholar-practitioner with over 15 years of experience who currently serves as Senior Researcher and Pillar Coordinator for Preventing Armed Conflict and Armed Violence at the United Nations Institute for Disarmament Research (UNIDIR) to reflect on what has been achieved, what work still lies ahead, and how women’s voices can take their rightful place at the heart of peace building efforts across the continent.

The dialogue opened with a shared acknowledgment: progress has been made, but the journey toward full gender inclusion in peace and security remains incomplete. Across Africa, there has been a noticeable shift in awareness and policy. More institutions have begun to integrate gender perspectives into recruitment, training, and peacekeeping frameworks. However, these shifts often remain surface-level occurring more formal compliance than as a deep restructuring of power, systems, and culture.

Women are increasingly present in peace building spaces, but their authority and influence are not always guaranteed. Participation has not automatically led to decision-making power. The conversation emphasized that while inclusion is important, influence is essential.

The session highlighted how women’s involvement in peace and security work reshapes the nature of engagement on the ground. Their presence often creates bridges where conflict has hardened divisions. Women draw on approaches rooted in empathy, cultural sensitivity, and lived community relationships qualities that can shift the tone and outcomes of peace efforts in constructive ways.

Communities respond differently when women lead. Trust deepens. Dialogue opens. Armed tensions soften. These are not theoretical claims but observations drawn from field experience across the continent. The value of women’s leadership is not symbolic it is strategic.

Despite these contributions, significant barriers remain. Many are structural: hierarchies, recruitment pipelines, policy frameworks, and institutional cultures that have historically privileged certain forms of leadership while overlooking others. Other barriers are deeply social and cultural tied to perceptions of whose voices are valid and whose expertise is recognized.

The discussion made clear that addressing these obstacles requires more than policy statements. It requires intentional leadership, sustained advocacy, the creation of mentorship pathways, and systems of accountability that ensure progress does not rely solely on individual passion or personal commitment.

Research also emerged as a critical area. Without data that documents what works, what fails, and why, change becomes difficult to measure or sustain. Evidence is needed not only to justify policies, but to protect gains from being reversed.

The session concluded with a renewed commitment to strengthen the Women, Peace and Security agenda for the next 25 years. The path forward calls for deepening women’s participation into real decision-making authority. It calls for reviewing existing policies to remove bias and outdated assumptions. It calls for training and sensitization that engage everyone because gender-responsive peace building is not a responsibility placed on women alone.

Equally important is the establishment of mentorship networks that nurture emerging women peace builders and ensure continuity of leadership across generations. Research must be prioritized, not as an academic exercise, but as a tool for shaping effective practice and protecting progress.

The future of peace building depends not on symbolic inclusion, but on dismantling the structural barriers that continue to limit women’s full and meaningful participation.